The year was 1935. America was starving, and in the hills of Appalachia, hope seemed gone. But while breadlines stretched long and factories stayed locked, a quiet army rose—not with weapons, but with books.

They were called the Book Women.

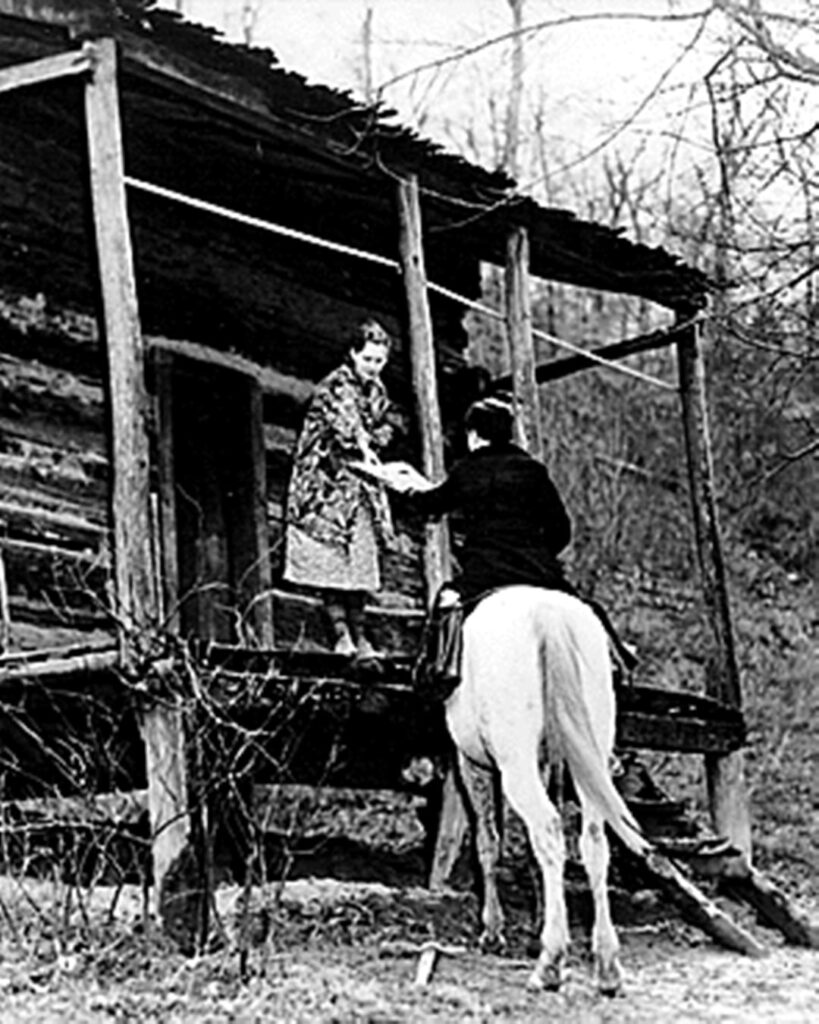

Daughters of miners, young mothers, widows—they saddled horses and mules, braving floods, blizzards, and miles of wilderness with nothing but grit and saddlebags stuffed with tattered novels, recipe books, almanacs, and magazines. Week after week, they rode 100 to 200 miles, carrying not food, but something just as vital: words.

Children waited on porches for stories to lift them out of hunger. Miners’ wives clutched cookbooks filled with hope scribbled in the margins. Farmers traced weather charts, dreaming of harvests that might save them.

By 1943, the war ended the program, but not before these women had delivered more than 100,000 books to 100,000 people. They weren’t just librarians. They were lifelines.

History remembers the Great Depression for its despair. But it should also remember the women who rode through the storm with stories that kept the human spirit alive.

To truly grasp the magnitude of their work, one must first understand the profound isolation of the land they served. The Appalachian Mountains of Eastern Kentucky were a world apart, a labyrinth of steep hills, called “hollers,” and winding creeks that often served as the only roads. In the 1930s, with the coal industry in collapse, poverty was not merely a condition; it was the very air the people breathed. Families lived in remote, hand-built cabins, miles from the nearest town, without electricity, running water, or access to schools. For many children, the world was no bigger than the valley in which they were born. This was an isolation that starved the mind as surely as the lack of food starved the body. It was into this crushing silence that the Pack Horse Librarians rode, their saddlebags a defiant promise of a world beyond the ridge line.

The program was a brilliant and resourceful component of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), designed to create jobs during the Depression. The logic was simple: if people couldn’t get to the library, the library would come to them. But its execution was anything but simple. The WPA could fund the librarians’ modest salaries—around $28 a month—but it could not pay for books, supplies, or libraries themselves. The entire literary payload of the project depended on charity. Books, magazines, and newspapers were donated from across the country, often arriving worn and damaged. The central “libraries,” usually housed in a church basement or a post office backroom, became workshops of literary restoration. Librarians and volunteers would spend hours mending torn pages with scraps of cloth, rebinding broken spines with whatever materials they could find, and carefully pasting over scribbles to make a text readable again.

For those who could not read, which included a significant portion of the adult population, the Book Women created something truly remarkable: scrapbooks. They would meticulously cut out pictures, recipes, quilting patterns, and interesting articles from donated magazines and paste them into binders. These scrapbooks became a form of visual literacy, a tangible connection to the culture, fashion, and news of the wider world. A woman could find a new pattern to brighten a worn dress or a new recipe to make meager rations feel like a feast. These handmade collections were among the most coveted items in the saddlebags, a testament to the librarians’ deep understanding of their patrons’ needs.

The daily routine of a Pack Horse Librarian was a testament to human endurance. Long before sunrise, she would be up, preparing her horse or mule, carefully balancing the weight of the books in her saddlebags to avoid injuring the animal. Her route was not a manicured path but a treacherous landscape. She forded swollen, icy creeks where a single misstep could mean being swept away. She navigated muddy trails that could suck a horseshoe right off a hoof and navigated steep, rocky inclines in blistering heat and blinding snow. The women faced suspicion from isolated mountain folk wary of outsiders and government programs, a mistrust they had to overcome with patience, consistency, and genuine care. They were not just delivering objects; they were building relationships, becoming trusted figures who brought not only literature but also news from neighboring communities, friendly conversation, and a listening ear.

Imagine the arrival of a Book Woman at a remote cabin. For children who had perhaps never held a new book in their lives, her appearance was an event of pure magic. They would run to meet her, their eyes wide with anticipation for the stories she carried—tales of adventure, fantasy, and faraway places that provided a precious escape from their daily hardships. The librarian would often stay and read aloud, her voice a comforting presence against the backdrop of a quiet, difficult life. For the adults, the delivery was just as vital. A copy of Popular Mechanics could give a farmer an idea for a new tool; a Bible, with its familiar passages, offered spiritual solace; a tattered copy of Robinson Crusoe was a reminder of resilience in the face of isolation. The books were read and reread, passed from hand to hand until they fell apart, their words absorbed into the very fabric of the community.

These women were more than couriers; they were educators and social workers on horseback. They were conduits of hope in its most tangible form. Their dedication went far beyond the requirements of a job. They knew the families on their routes intimately—they knew who was sick, who was struggling, and which child had a particular thirst for stories about animals or pirates. Their work affirmed a powerful idea: that economic poverty should not lead to intellectual or spiritual poverty. They believed that everyone, regardless of their station or location, deserved access to the dignity, escape, and empowerment that reading provides.

When the WPA was disbanded in 1943 to divert resources to the war effort, the Pack Horse Library Project came to an end. The book routes vanished, and the steady clopping of hooves carrying literary treasures faded from the mountain trails. Yet, the legacy of the Book Women endured. They had planted seeds of literacy and curiosity that would blossom for generations. They demonstrated the profound impact of bringing resources directly to the people who need them most. In a chapter of American history defined by what was lost, the story of these librarians is a powerful narrative of what was built, what was shared, and what was saved. They stand as unsung heroes, a quiet army whose weapons were words, and whose victory was the preservation of the human spirit against the greatest of odds.

The year was 1935. America was starving, and in the hills of Appalachia, hope seemed gone. But while breadlines stretched long and factories stayed locked, a quiet army rose—not with weapons, but with books. They were called the Book Women. Daughters of miners, young mothers, widows—they saddled horses and mules, braving floods, blizzards, and miles of wilderness with nothing but grit and saddlebags stuffed with tattered novels, recipe books, almanacs, and magazines. Week after week, they rode 100 to 200 miles, carrying not food, but something just as vital: words. Children waited on porches for stories to lift them out of hunger. Miners’ wives clutched cookbooks filled with hope scribbled in the margins. Farmers traced weather charts, dreaming of harvests that might save them. By 1943, the war ended the program, but not before these women had delivered more than 100,000 books to 100,000 people. They weren’t just librarians. They were lifelines. History remembers the Great Depression for its despair. But it should also remember the women who rode through the storm with stories that kept the human spirit alive.